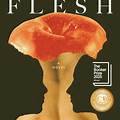

Flesh by Hungarian-British author David Szalay was recently announced as the winner of the 2025 Booker Award. Although the Booker board called it “a propulsive, hypnotic novel about a man who is unraveled by a series of events beyond his grasp,” I found it hard to get into. At best, I saw its protagonist, then-15-year-old Istvan, as an expression of an aspect of contemporary masculinity: alienated, apathetic, inarticulate, defined by a sense of powerlessness.

Istvan lives with his mother in a large apartment complex in Hungary. He grudgingly accepts her demand that he regularly help an older resident bring home bags of groceries from the local market. The “older woman” turns out to be 42 years old, and, over time, she seduces him. His conversational skills are limited to grunts, answering questions with monosyllabic questions like “yeah?” and learning from her the tools of sex with near-total lack of agency. In this, as in others of his relationships, sex is presented solely as an animal function, never equated with love and rarely paired with introspection that leads to self-understanding.

In the earliest chapters, the reader gets no sense of Istvan’s interior life or, indeed, if he has one at all, even when he does time at a juvenile institution in the wake of the seducer’s husband’s death in a lethal fall in the apartment building. His incarceration taught him only that he was capable of being a fighter.

He later enlists in the army and serves five years in Iraq. By now, we are getting drawn more deeply into his story. Persuaded to see a therapist to deal with what is clearly PTSD, Istvan has a vague sense that war violence and the death of a friend have changed his life but, even with the therapist, he is hard put to articulate why.

Heavy smoking, excessive use of alcohol and abundant illegal drugs are themes across the ensuing years, as his life moves propulsively through jobs as a bouncer in a sleazy pole-dance bar, an employee of a private security company, then as a bodyguard and driver for ultra-wealthy private individuals. That role requires him to learn how to dress in suits, improve his boorish behavior, and move discreetly in different circles. But his exterior changes don’t reflect similar development of his thought processes, his understanding of why he does certain things. The reader wonders more about where his passivity – just waiting for things to happen to him – will lead him than does Istvan himself, who seems to have no regard for his future at all.

The setting lurches from Budapest to London. He gets drawn into a sexual relationship with his wealthy employer’s wife (simultaneously with a side affair with another member of the corporate titan’s staff). I won’t go into where this all takes him, his rise into the world of material wealth, or where he ends up.

In many ways, Istvan’s relationships echo that of his first sexual encounters as a 15-year-old. In one of his rare reflective moments, he says that, with women, “It’s hard to have an experience that feels entirely new, that doesn’t feel like something that has already happened, and will probably happen again in some very similar way, so that it never feels like all that much is at stake.” Good grief!

In middle age, Istvan’s potential to be more than a rote sexual animal becomes clear when he becomes a father and, perhaps for the first time, shares a little interior emotion. He hopes that adolescence for his pre-teen son will be less stressful than the years of his own burgeoning physicality. But, when tragedy strikes, he sinks deeper into alcoholism. As he ages, he begins to understand that his life has been changed by a handful of people who have played roles in it, but he never gets to the point of being able to express, even to himself, exactly what that process has entailed.

This is a dark book. It has a way of pounding from one stage of Istvan’s life to the next, with our grasp of events revealed often after the fact. It is a world of empty people, of understanding only through often meaningless physical experiences, of loneliness and anger.

Ultimately, I came to understand the Booker board’s decision. Szalay’s writing style is minimalist, his sentences truncated, replicating how stunted Istvan himself is emotionally. The spare prose sadly captures an emptiness experienced by too many men today. Flesh fosters an understanding of what drives a large cohort of alienated people in today’s fraught political world and is an important, if difficult, book to read.

I welcome your feedback in the comments section. Click upper left to return to the home page then hit “Leave a Comment.” Book recommendations welcome. To be alerted when a new blog is posted, look for “Follow’ in the upper right portion of the home page, enter your email and click on subscribe. If you enjoy reading my blog, please share it with friends.